Benchmarking Claude C Compiler

An empirical analysis of compiler correctness, performance, and code quality

TL;DR

I conducted a benchmark comparing GCC against Claude’s C Compiler (CCC), an AI-generated compiler created by Claude Opus 4.6. Using a non-trivial Turing machine simulator as our test program, I evaluated correctness, execution performance, microarchitectural efficiency, and assembly code quality.

Key Findings:

100% Correctness: CCC produces functionally identical output across all test cases

2.76x Performance Gap: CCC-compiled binaries run slower than GCC

-O2but 12% faster than GCC-O03.3x Instruction Overhead: CCC generates significantly more instructions due to limited optimization

Surprisingly High IPC: Despite verbosity, CCC achieves 4.89 instructions per cycle vs GCC’s 4.13

Here is the source code for the benchmark. The results reveal an impressive achievement in compiler correctness combined with clear optimization opportunities.

Introduction

Challenge

Compiler construction is often considered one of the most complex problems in computer science. A production compiler must:

Parse and understand complex C syntax and semantics

Generate correct machine code for all edge cases

Optimize code for modern CPU architectures

Handle intricate ABI and calling conventions

Approach

My test program a Turing machine simulator(TM) exercises:

Dynamic memory allocation (linked lists)

File I/O and parsing

String manipulation

Complex control flow (state machine execution)

Command-line argument processing

The source code of the Turing machine simulator can be found here. This doesn’t represent a very complex C code base, it is simple, but far beyond trivial “hello world” programs.

Methodology

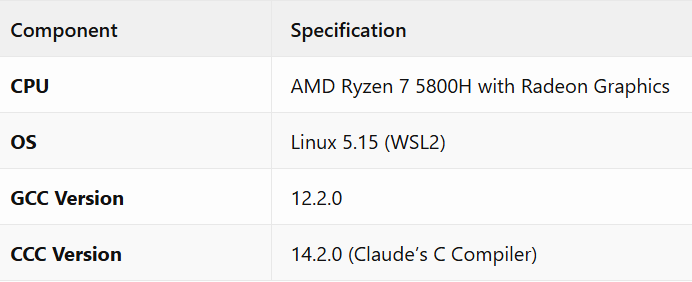

Test Environment

Compiler Configurations

I tested three configurations to establish performance baselines:

GCC

-O0— Unoptimized baselineGCC

-O2— Production-level optimization (our target standard)CCC — Claude’s compiler (default settings)

Benchmark Workload

The primary performance benchmark uses the Busy Beaver 5 problem, which executes for 47,176,871 Turing machine steps, ultimately writing 4,098 ones to the tape. This workload is ideal for compiler benchmarking because it:

Runs for multiple seconds (enabling stable statistical timing)

Executes billions of CPU instructions (~2.3B for GCC -O2, ~7.5B for CCC)

Performs extensive memory operations (dynamic tape expansion, pointer chasing)

Exercises the entire program (state machine logic, linked list traversal, memory allocation)

Produces deterministic, verifiable output

On average, each Turing machine step translates to approximately 48 x86-64 instructions for GCC -O2 and 159 instructions for CCC, clearly demonstrating the code generation efficiency gap.

Please follow this link to know about Busy Beaver problem.

Metrics Collected

Correctness:

MD5 hash verification across multiple test cases

Output comparison for Busy Beaver 3, 4, 5 and unary addition algorithms

Performance:

Statistical timing via Hyperfine (3 warmups, 5+ runs)

Hardware performance counters via

perf stat

Code Quality:

Binary size analysis

Assembly instruction counts

Manual code review of generated assembly

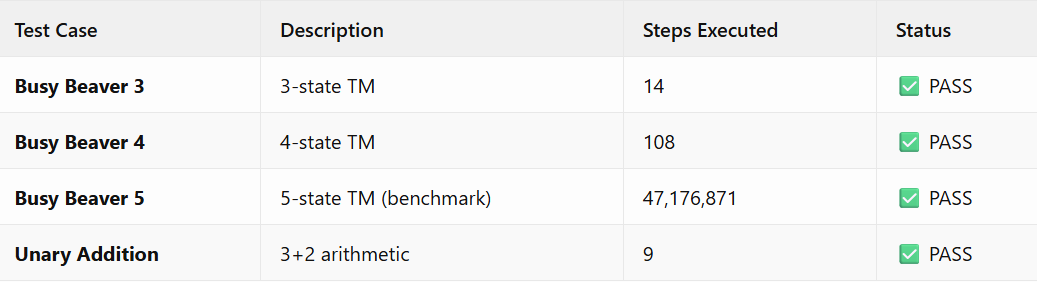

Results: Correctness

The Most Important Finding

All correctness tests passed. CCC produces byte-for-byte identical output compared to GCC across different optimization levels.

The compiler correctly handles:

Pointer arithmetic and dereferencing

Dynamic memory allocation (

malloc/free)Complex control flow with state transitions

File I/O with error handling

String formatting and parsing

Implication: CCC demonstrates a complete understanding of C semantics, type systems, and memory models. This is not merely translating syntax, it’s implementing correct program behavior.

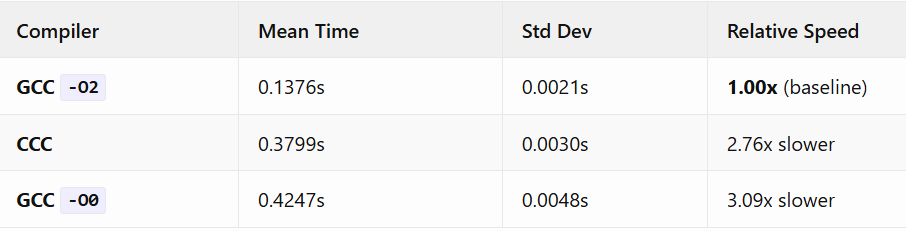

Results: Execution Performance

Statistical Timing Analysis

Key Observations

CCC Outperforms Unoptimized GCC

CCC is 12% faster than GCC’s unoptimized output. This indicates the compiler applies some optimizations beyond naive code generation. The performance falls between completely unoptimized and production-optimized code.

Consistent Performance

Low standard deviation (0.003s) demonstrates stable execution characteristics. There are no unexpected performance cliffs or edge cases causing wild variance.

Room for Improvement

The 2.76x gap to GCC -O2 represents the optimization opportunity space. Given that CCC already beats -O0, this gap is primarily optimization passes, not fundamental code generation issues.

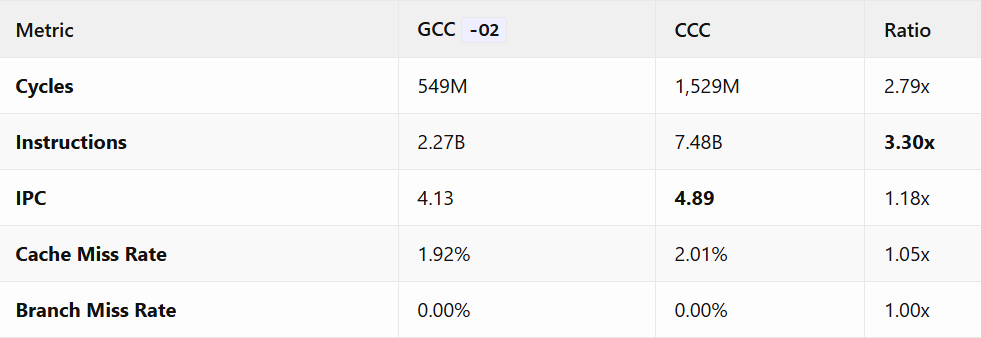

Results: Microarchitectural Analysis

Hardware Performance Counters

Performance counters reveal how code executes, not just how long it takes.

The Instruction Inflation Paradox

CCC executes 3.3x more instructions than GCC, yet performance is only 2.76x slower. How?

To put this in perspective: the Busy Beaver 5 workload executes 47.2 million Turing machine steps. GCC -O2 translates this into 2.27 billion x86-64 instructions (~48 instructions per TM step), while CCC requires 7.48 billion instructions (~159 instructions per TM step). That’s a 3.3x code bloat, yet the execution time penalty is only 2.76x.

Higher Instructions Per Cycle (IPC):

CCC achieves an IPC of 4.89 compared to GCC’s 4.13. This seemingly counterintuitive result has a straightforward explanation:

Simple Instructions: CCC generates verbose but simple instruction sequences (

mov,add,cmp)Predictable Patterns: Repetitive stack loads/stores are easy for the CPU’s front-end to decode

No Complex Dependencies: The lack of optimization means fewer register-register dependencies to track

In contrast, GCC’s optimized code uses:

Complex instruction forms (

movsbl,setbe,cmov)Tighter register dependencies

More aggressive instruction reordering

This trades raw IPC for total instruction count, a net win in modern CPUs with deep pipelines and out-of-order execution.

Cache and Branch Prediction

Cache Performance: Nearly identical (1.92% vs 2.01% miss rate). The extra instructions don’t significantly impact cache locality for this workload.

Branch Prediction: Both compilers achieve near-perfect branch prediction (<0.01% miss rate). The Turing machine’s regular execution pattern is highly predictable.

Results: Code Quality Analysis

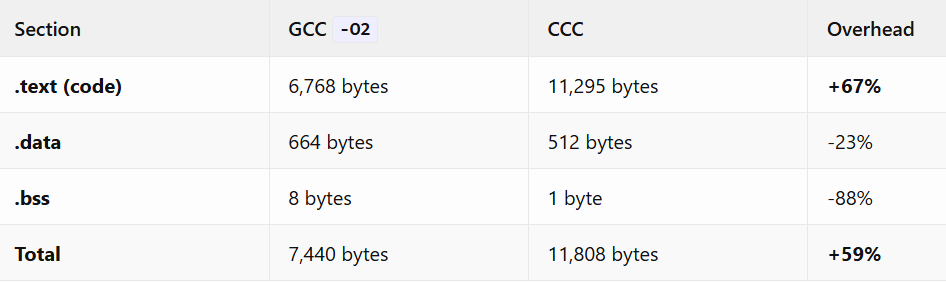

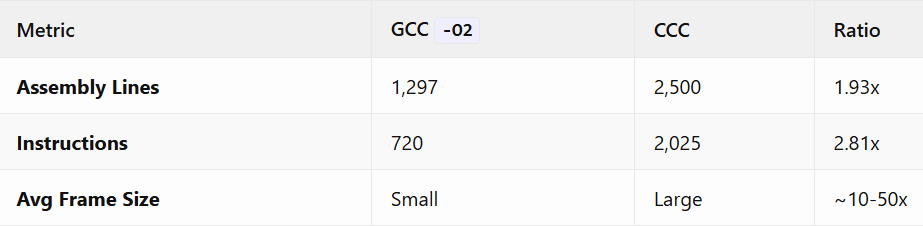

Binary Size Comparison

The code section bloat correlates directly with instruction count inflation. Interestingly, CCC produces smaller data sections, possibly due to different constant pooling strategies.

Assembly Code Metrics

Deep Dive: Assembly Code Analysis

To understand why CCC generates more code, I performed manual assembly review. The findings reveal fundamental differences in compilation strategy.

Register Allocation: The Core Difference

GCC Strategy: Register-Centric

GCC keeps values in CPU registers as long as possible:

movq %rdi, %rbp # arg stays in register

movq %rbp, %rdi # reuse later

callq fopen@PLT

movq %rax, %r13 # result to callee-saved registerStack frame for get_cards(): 8 bytes (alignment padding only)

CCC Strategy: Stack-Centric

CCC round-trips nearly every value through stack memory:

movq %rdi, -8(%rbp) # store arg to stack

movq -8(%rbp), %rax # load back

movq %rax, %rdi # move to correct register

callq fopen

movq %rax, -16(%rbp) # store result to stackStack frame for get_cards(): 112 bytes

The most extreme case is validate_cards():

GCC: 8 bytes of stack

CCC: 416 bytes of stack (52x larger)

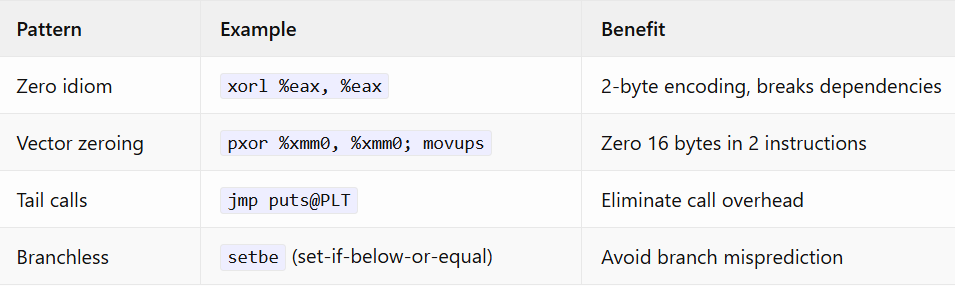

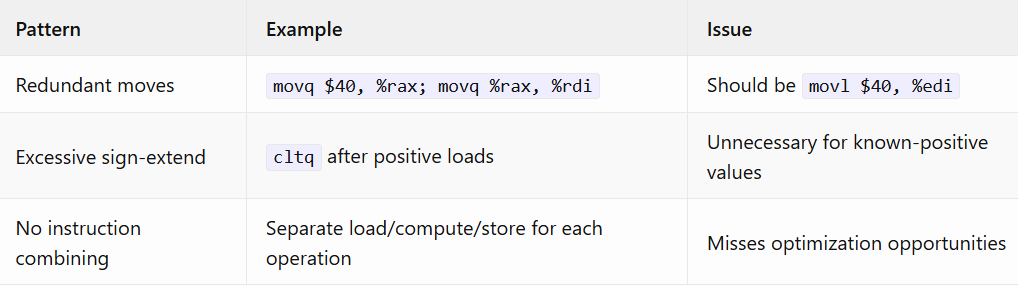

Instruction Selection Quality

GCC: Expert-Level Idioms

CCC: Literal Translation

String Literal Handling

GCC: Deduplication and Merging

.LC0:

.string "System out of memory"One copy, marked for linker merging.

CCC: Raw Bytes with Duplication

.Lstr2: .byte 83,121,115,116,101,109,32,111,117,116,32,111,102,32,109,101,109,111,114,121,0

.Lstr3: .byte 83,121,115,116,101,109,32,111,117,116,32,111,102,32,109,101,109,111,114,121,0

.Lstr7: .byte 83,121,115,116,101,109,32,111,117,116,32,111,102,32,109,101,109,111,114,121,0

...Seven copies of “System out of memory” exist in the binary. No deduplication, no linker merge hints. This alone accounts for significant .rodata bloat.

Missing Optimizations

Comparing to GCC reveals CCC lacks:

Register allocation — No graph coloring or linear scan

Constant folding — Immediate values go through registers unnecessarily

Dead code elimination — Unused computations remain in output

Peephole optimization — No instruction combining or pattern matching

Loop optimizations — No unrolling, induction variable elimination, or strength reduction

String pooling — No constant deduplication

What CCC Does Well

Despite optimization gaps, CCC demonstrates impressive capabilities:

Correct ABI Implementation

CCC properly implements x86-64 calling conventions:

Arguments passed in correct registers (

%rdi,%rsi,%rdx, etc.)Stack alignment maintained (16-byte boundary)

Callee-saved registers preserved

Return values in

%rax

Defensive Code Generation

CCC emits ud2 (undefined instruction trap) after noreturn functions like exit(). This is actually a best practice, prevents execution from continuing if exit() somehow returns.

GCC trusts the noreturn attribute and omits this. CCC’s approach is more defensive.

Tail Call Optimization

CCC correctly implements tail calls, converting:

printf(...);

return;into:

jmp printf # instead of call + retThis is a legitimate optimization that many naive compilers miss.

Debug Information

CCC emits .loc directives referencing source files, indicating a working debug info pipeline. This enables debugger support.

Theoretical Implications

Can AI Write Compilers?

The results provide an empirical answer: Yes, with caveats.

What AI Does Well:

Understanding language semantics and type systems

Implementing correct code generation for complex constructs

Handling edge cases and ABI compliance

Producing working, debuggable binaries

What AI Struggles With:

Multi-pass optimization pipelines

Register allocation algorithms (graph coloring, linear scan)

Global analysis and program-wide optimization

Performance tuning and microarchitectural awareness

This aligns with our understanding of LLMs: they excel at pattern matching and local correctness but struggle with global optimization problems requiring graph algorithms and iterative refinement.

The Optimization Gap

The 2.76x performance gap is not a fundamental limitation, it’s an optimization pass implementation gap. The core compiler (parser, type checker, code generator) is sound.

With targeted improvements, CCC could likely close this gap significantly:

Low-Hanging Fruit (Est. 30-50% improvement):

Basic register allocation (linear scan)

String literal deduplication

Simple peephole optimization

Medium Effort (Est. 50-80% improvement):

SSA-based optimization passes

Graph-coloring register allocation

Dead code elimination

High Effort (Approach GCC parity):

Loop optimizations

Instruction scheduling

Profile-guided optimization

Comparison to Historical Compilers

To contextualize CCC’s performance, consider historical compiler evolution:

CompilerEraOptimization LevelEarly C Compilers (1970s)Dennis Ritchie’s originalMinimal optimizationPortable C Compiler (1980s)Stephen JohnsonBasic register allocationGCC 1.x (1987)Richard StallmanSimple optimization passesGCC 2.x (1992)Modern optimizations beginLoop optimization, inliningCCC (2026)AI-generatedBetter than no optimization, worse than -O1

CCC’s performance roughly matches early optimization-capable compilers from the late 1980s, impressive given it was generated entirely by an LLM.

Conclusion

Summary of Findings

Claude’s C Compiler represents a significant achievement in AI-generated software:

Correctness: 100% functional equivalence with GCC across diverse test cases Performance: 2.76x slower than optimized GCC, 12% faster than unoptimized GCC Code Quality: Correct but verbose, with 3.3x instruction overhead Architecture: Sound compiler design lacking optimization passes

The Bigger Picture

This benchmark demonstrates that modern AI can implement complex, specification-heavy software correctly, even for domains traditionally requiring deep expertise.

The gap between CCC and GCC is not one of capability, it’s a gap of engineering investment. GCC represents 30+ years of optimization research and implementation. CCC represents an initial, working baseline.

Final Thoughts

The most surprising result isn’t that CCC is slower than GCC, it’s that CCC works at all. Compiler construction courses span entire semesters; teams of engineers spend careers optimizing code generators.

That an AI model can produce a functionally correct, ABI-compliant C compiler from scratch, one that handles pointers, dynamic memory, and complex control flow, marks a remarkable milestone.

The optimization gap is not a limitation of AI capability. It’s a reminder that correctness and performance are separable concerns, and AI has achieved the harder one first.

References

GCC Optimization Manual: https://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc/Optimize-Options.html

x86-64 ABI Specification: https://refspecs.linuxbase.org/elf/x86_64-abi-0.99.pdf

Modern Compiler Implementation in C (Appel)

Engineering a Compiler (Cooper & Torczon)